I have yet again failed to keep this updated all summer. Even though I have an extra battery in my car which basically allows me to charge my laptop anytime I want, the whole working 6-7 days a week and not having internet really made me lazy about writing blog posts. So as I did at the end of last summer I will try to summarize the fun and interesting parts of the field work, but mostly just include the best photos.

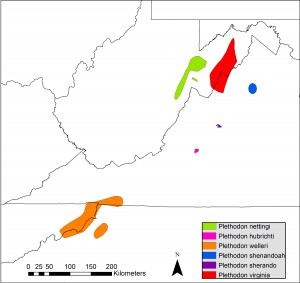

The field season was broken into two time frames. A brief 9 day trip in May with my two field assistants from last year, William Ternes and Celeste Wheeler, and myself, where we covered some low elevation sites in North Carolina and Tennessee and we also visited Plethodon sherando field sites up in Virginia. This first trip was pretty uneventful. We were able to collect data to help support a project that we hope to have submitted for publication later this year. My two co-authors Will and Celeste present a poster on this project which compares habitat use of the microendemic P. sherando to the widespread P. cinereus, at the annual Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists which occurred at the end of the summer in Chattanooga, TN.

Celeste and Will presenting our poster at the Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists – July 30th-August 3rd

After this first field work trip, we all ventured to a the 6th Plethodontid conference. We joined several other people from Ohio University and drove a van together down to Tulsa, OK. This conference only happens every 5-10 years, so it was really a treat to get to participate.

The second field work trip happened immediately after the Plethodontid conference. Celeste moved on and went to Arizona to work on tree lizards with my former lab mate Matt Lattanzio. However, Will Ternes continued on with me and we also added on TWO new field assistants Kristie Warak and Rebecca Wier. Both Kristie and Becca met me at the start point of our second trip which was Bear Heaven campground near Elkins, WV. This second leg started at my northern most sites in West Virginia and weaved south down the Appalachian Mountains into the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in North Carolina and Tennessee.

I think it will be best to summarize how the summer went and then show some photos of the coolest animals.

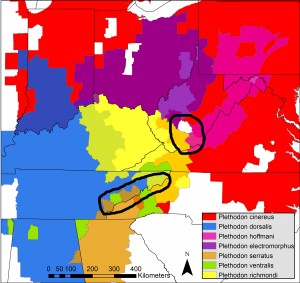

First off, I added some new sampling this summer. Previously, I had relied on range maps to determine species richness. However, this really doesn’t paint an accurate picture especially for microhabitat work. Therefore, I started doing time constraint searches at all of my sites. This included 1 person hour of search during both the day and night. After searching we then completed microhabitat data collection at 10 random locations. So for each site I currently have two searches and 20 random microhabitat data points. This will hopefully be continued next year so I can add more searches and more microhabitat points which will help me assess if variability in microhabitat promotes species diversity. The night surveys allowed us to observe some cool events such as tons of climbing salamanders. When people think salamanders they normally think of streams. So when I tell them that there are tons of them in the forest living in the leaf litter they are normally pretty shocked. It is even harder to convince people that they actually come out in huge numbers and even climb meters off the ground on the right nights! We also saw salamander emerging from within big decaying logs. This site reminded me of Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark when Indiana Jones is in the pit with snakes coming out of holes in the walls….only with salamanders.

Desmognathus emerging from a log at night in northeast Tennessee

Other than that addition, everything was the same as last year. I continued to sample 1 meter square microhabitat plots with and without salamanders. The number of plots completed is now over 500 which is almost double from the previous two years.

Now for the photos, I think it will be easier to break this up into taxonomic groups rather than by location since I am not 100% positive where each salamander (or other animal) came from. I could look this up using the dates but for this purpose I don’t think it is necessary. If you want more information on any of the animals just let me know, because I probably have a lot more data than what I am presenting here. Also, as a disclaimer, I added in common names for most species, but some I left out. If you want to know the common name for anything that I did not list, just let me know.

First the reptiles! The reptiles are going first because it was a fairly uneventful reptile year with a few exceptions. We only saw a few lizards and I only managed to photograph one. However, I am pretty sure we found a Coal Skink which would have been a lifer for me and very cool, but I did not get photos so I can not be positive on the ID! The one skink I did get a photo of was just a juvenile skink, I am guessing it is a common five-lined skink (Plestiodon fasciatus), but I do not know my skinks well enough to be sure as many of them look similar especially when they are young.

Juvenile skink found in northern Virginia

We also saw several cool snakes, but the only species that was new (for my dissertation field work) was a copperhead. We found two copperheads, the first was at a field site sitting next to a stream. The snake was relatively small and did not move despite being photographed for 30 minutes. I did not move the snake, we just watched it hang out and observed him for a bit. The second copperhead was found in the middle of the Blue Ridge Parkway by Becca and Kristie. This snake was, to put it lightly, very unhappy. It is possible that Becca’s car straddling over him caused him to be a bit angry. He struck at us a lot but we eventually got him off the road.

Copperhead found at a field site

Copperhead found on the Blue Ridge Parkway

Both of the copperheads were found very early in the year, but we had a pretty long delay before out next major snake find. We saw several black rat snakes, garter snakes, ring neck snakes, but no other uncommon or really neat species until the very last night. Driving home on our last night out in the field in the Great Smoky Mountains we drove up on a juvenile timber rattlesnake!! I thought it was a great way to finish off the field season.

Timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) found on the Blue Ridge Parkway in North Carolina

Now on to the bulk of the cool stuff found this summer, the salamanders! I mean I am studying them so I would hope most of the cool and rare things found during my work would be salamanders. Again, I will break this up into different groups, starting with Desmognathus. Desmogs are the group I find the most interesting, but they are also some of my least favorites just because I still find it incredibly difficult to identify them. As I discussed in my previous post, there is extreme variation in color and pattern in many Desmog species. The easiest to identify species are the tiny ones and the huge ones like the Pygmy and Black-bellied salamanders.

Pygmy Salamander (Desmognathus wrighti), the smallest Desmognathus and close to if not the smallest salamander in the US

Pygmy salamander (Desmognathus wrighti) with my hand for size comparison

Black-bellied salamander (Desmognathus quadramaculatus), the largest Desmog to compare with the smallest Desmog pictured above.

Desmog sp. with eggs

Desmog sp. (I think D. ocoee)

Desmog sp. (I think D. santeetlah)

Desmog sp.

The next group of salamanders I want show you are the Pseudotriton, although I only found red salamanders (Pseudotriton ruber), but we found a many of them. I think we only found one red salamander last year. This year we found bunches including one site where we found 4 different individuals including some pretty interesting color variation. I know these guys are pretty common and have a pretty extensive range, but they are one of my favorites to find because they are not as common to find just flipping cover objects and looking through leaf litter, normally you need to search in muddy or mucky areas to have the best luck. Plus, they are gorgeous, and it is a nice change from finding small bodied Plethodon species all day. So overall I am glad we got to find so many this year, and I also got to add several data points for this species which was fairly unexpected.

Pseudotriton ruber

Pseudotriton ruber from near Sherando, Virginia

Pseudotriton ruber from near Peaks of Otter, Virginia

Pseudotriton ruber from near Peaks of Otter, Virginia

Two Pseudotriton ruber from near Peaks of Otter, Virginia

We also found many of the more common species, but I did not focus on taking photos as much this summer so I only have a few good photos of the genera that are not as prevalent in my research plots including the eft stage of the red spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens).

Slimy salamander species and Eastern red-spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens)

Eastern red-spotted newt (Notophthalmus viridescens)

Southern two-lined salamander (Eurycea cirrigera)

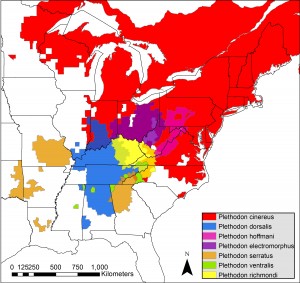

The next group is probably the most important to my research as they are typical terrestrial group of plethodontid salamanders, the Plethodon species (plethodontid refers to the family Plethodontidae, where Plethodon is a genus within this family). The other genera of Plethodontids are typically more aquatic with a few exceptions such as the pygmy salamander (Desmognathus wrighti) which is completely terrestrial including direct development. However, most other plethodontids spend a good portion of their life in or very near water. I also went out of my way to find some extra cool species, including Weller’s salamander (Plethodon welleri) which is restricted to high elevation spruce habitat within its relatively small range. Overall I am pretty sure I found more species than I have in any other previous years (I have to confirm with my data on that), but some of it was just for fun and was not always research related. I think I took off maybe 6 or 7 days all summer and every one of them except for a one day trip to Asheville, NC involved looking for salamanders. You know how you know you love what you do? When you go and do what you do for fun when you take a break from doing it for work. The photos below are the cream of the crop, all the cool species that have either restricted ranges or just look fantastic.

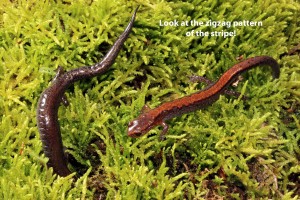

Plethodon yonahlossee, probably my favorite Plethodon

Plethodon yonahlossee

My first Plethodon welleri, extremely cool species, I wish I was able to see more, perhaps next year

Plethodon wehrlei were fairly common at my West Virginia sites

This Plethodon wehrlei was found a few feet from my tent at our very first campsite

Plethodon teyahalee is found in the southern Appalachians and can hybridize with several other species

The Big Levels salamander (Plethodon sherando) is only found within a small area of Augusta County, VA

Plethodon nettingi also have a somewhat restricted range, found at high elevations typically in spruce habitat in West Virginia

This is probably one of the best photos of the summer simply because the Peaks of Otter Salamander (Plethodon hubrichti) is not a fan of sitting still. They also have a very restricted range as you can see in my previous posts about identifying Plethodon species.

These final two animals were not research related, but they are both extremely cool animals that I have always wanted to see.

The first is the Cave Salamander (Eurycea lucifuga). This species can certainly be found outside of caves, but they are much more prevalent in and around them. I was able to see this guy at a cave near Mountain Lake Biological Station (5-10 miles away). He was found outside the cave entrance, but from what I have heard inside the cave it is routine to see 20+ cave salamanders, or going out at night many individuals can be seen outside the cave. I was lucky and able to see this guy outside in the middle of the day.

Very over saturated Eurycea lucifuga photo

Very gorgeous Eurycea lucifuga

The finally species I will include in this post is the coolest animal I have ever seen in the wild. I have certainly been a snake person most of my life, but this salamander just blew me away. When I reported the sighting to NC Wildlife Resources Commission (they request this on their information sheet on the species), I was told the area I was in is a hot spot for the species. I am of course referring to the great and mighty Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis). This species is still common in streams and rivers that meet its habitat requirements, but it is certainly declining through much of its range. It was a pleasure to get to see them. It really makes me want to find a way to research this awesome species if I can get the chance. For the moment I am just glad I was able to see them in the wild (I saw two at this location).

The great, the amazing, Hellbender (Cryptobranchus alleganiensis)

Overall, it was a great summer, I collected a bunch of data, I saw a ton of very cool animals, and everything went smoothly. I want to thank my field assistants Will Ternes, Kristie Warak, and Becca Wier who were big helps this summer. I am looking forward to one more final year of field work which will most likely include some work this fall and extensive work next spring and summer. After that I will be able to focus on writing and finishing up the dissertation. So for now, I hope you enjoyed the photos. If you have any questions feel free to ask! I will hopefully follow up with some posts about this falls field work and maybe one or two on the field ecology lab I will be teaching this semester. Happy herping!