Before I start the bulk of my field work I wanted to make a post on the small bodied Plethodon species of the eastern US and include some ways to help identify them without going through a key. There are plenty of quality resources for identifying these species with using typical identification keys (I will provide a list of good guides at the end). However, for the casual hiker/herp this isn’t always realistic as identifying some of these key morphological features require a lot of handling. Small salamanders can overheat and die VERY quickly, so it is ideal to avoid handling them, especially for more then a couple minutes. Also, if people know you are found of reptiles and amphibians (at least in my experience) they will often send you photos asking for identification help which often makes using a key impossible. Therefore, being able to offer a educated guess with general morphological characteristics and geographic location can be very handy. Plethodon species aren’t as difficult to identify as members of the Desmognathus genus, but, especially for the casual naturalist, small Plethodon species (e.g. compared to large bodied glutinous species groups) can be difficult to tell apart. Before I go any further, I would like to thank Todd Pierson for letting me use some of his photos, you can tell which photos are his as they contain his name and they are also substantially better then any of mine.

Just to reiterate, the goal here is to offer ways to narrow down species identification when information is limited to the salamanders location (possibly habitat) and only general knowledge of the salamanders appearance. Also, a key thing to mention, that people unfamiliar with salamanders may not know, there can be SUBSTANTIAL color variation in many species. One of the most variable species is the red-backed salamander, which have many color variants that to the untrained eye will look nothing like photos found in field guides. However, most of these extreme color and pattern differences are uncommon, but be aware they do occur. The most common color variation found in Plethodon species is the presence or absence of a dorsal stripe. Plethodon cinereus, Plethodon serratus, Plethodon sherando, Plethodon shenandoah, Plethodon ventralis, and Plethodon dorsalis all exhibit this dorsal stripe polymorphism. However, using locality information and other characters it should be possible to distinguish between most of these species.

I know some people will not be familiar with scientific names, but I get in the habit of using them. So to avoid confusion, here is a table of scientific names with their respective common names.

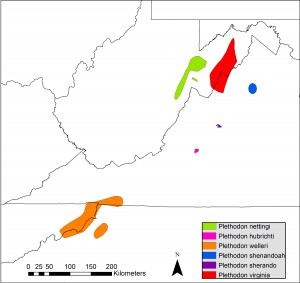

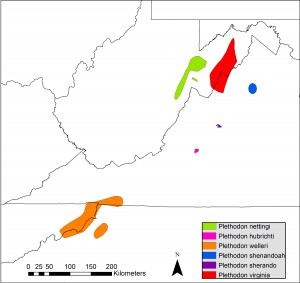

I am also going to include a few range maps, all of them are high resolution so it is best to click on them and zoom into them in a new window. The first shows species that have very limited ranges and in many cases are the only small bodied Plethodon species present where they occur.

Starting at the southern most species on this first map, Plethodon welleri, which exists primarily at high elevations and spruce-fir forests. This species can be present as low as 800 meters elevation, but they are primarily found much higher, closer to 1,500 meters. However, this is an easily to identify species as they are pretty distinct from other Plethodon in the area. They have an overall dark color to their body but they are covered with gold/brassy blotches. They are a very gorgeous species (I am still waiting to find my first). There are not many species that can be confussed with Plethodon welleri. Other species may have brass or gold flecking, but it will not be as pronounced.

Further north in Virginia we find the Peaks of Otter salamander, Plethodon hubrichti. This species actually somewhat resembled Plethodon welleri, in that it also has a dark body covered with gold/brass coloration. However, where as Plethodon welleri has more pronounced blotches, Plethodon hubrichti has smaller fleckings of color. Also their ranges do not even come close to overlapping. The Peaks of Otter Salamander is only found in Bedford and Botetourt counties making them fairly easy to identify with locality information.

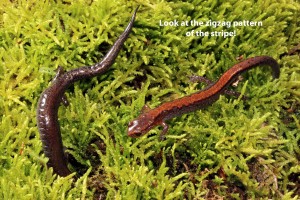

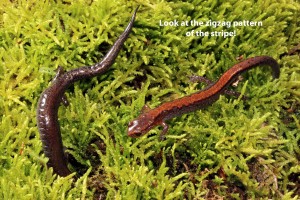

Still working our way north we find the Big Levels Salamander, Plethodon sherando, which looks almost identical to Plethodon cinereus. This is where there can be some real confusion. However, the only places Plethodon sherando has been found is Augusta and Nelson County, Virginia. So unless you are in these counties, you have most likely not found this species. The only major characteristic that easily separates them from Plethodon cinereus is a shorter trunk and longer limbs. Personally, I found after seeing several of them that it was pretty obvious, however the official way to demonstrate this is to count the costal grooves between adpressed limbs. This is a fancy way of waying you bend the front limb backwards and the rear limb forward so the digits are pointing towards each other. Then counting the costal grooves along the body between the digits. As you can imagine this is very difficult to do with a live salamander. Measurements of salamanders we found a few weeks ago seem to also indicate that the shorter truck also means the tail will be proportionally longer, so that is another characteristic that can be eyeballed. Also there is only a small area of overlap between the species, so if you are at a location under 579 meters of elevation you can be pretty sure it is Plethodon cinereus and not Plethodon sherando. In contrast, if you are within the species range indicated on the map, and above 630 meters you can be more confident that it is a Plethodon sherando. As the below image shows you can see they are very similar, but the longer limbs and shorter trunk are somewhat apparent on the Big Levels Salamander (top) when shown in contrast to the shorter limbed longer trunked Eastern Red-backed Salamander (bottom).

The three northern most species on the map includes one federally threatened and one endangered species. Plethodon nettingi (northwesten most species on the map) is threatened primarily due to their small range and that they are found almost exclusively in areas with spruce and hemlock at high elevations (above 750 m). Similar to the Peaks of Otter Salamander, the Cheat Mountain Salamander has a dark body with color flecking on the dorsum (it’s back). However, where as the Peaks of Otter Salamander pretty much always has brass or gold flecking, the Cheat Mountain Salamander ranges from brass to white or silver flecking. Again, the ranges of these two species do not even come close to overlapping, so knowing where you are is more than half the battle in identifying them. In my experience it can look very similar to a Peaks of Otter Salamander, or it can almost look like a slimy salamander with lots of white/silver spots, except the spots are very tiny on the Cheat Mountain Salamander (adult Slimy Salamanders are also much larger), making them pretty distinguishable from any other salamander in the area.

Farther east we find the federally endangered Shenandoah Salamander (Plethodon shenandoah). As this species is endangered, I have no photos of them, however the only species that is easily confused with them in their range is, like is the case for many other species, the Eastern Red-backed Salamander. They should be pretty easy to tell apart as the Shenandoah Salamander has a narrower dorsal stripe, and more importantly a uniformly black belly, compared to the salt and pepper belly of the Eastern Red-backed Salamander.

Between the Cheat Mountain Salamander the Shenandoah Salamander we come across the Shenandoah Mountain Salamander (Plethoodn virginia, yes it is different than the Shenandoah Salamander) which was recently described by Highton in 1999. This species was previously lumped in with the Valley and Ridge Salamander (Plethodon hoffmani). Plethodon hoffmani is on the range map below and does overlap with this newly described Plethodon virginia. These are probably one of the trickiest two species to identify for the lay person. Without genetic analysis or a detailed geographic information it will be near impossible to tell them apart. Basically if you are in far the far eastern part of West Virginia near the border of Virginia, you may be in the range of Plethodon virginia, however if you are in Maryland, Pennsylvania, or western West Virgina or Virgina, then you are most likely looking at Plethodon hoffmani. As with many of these species they can be confused with the lead back phase of Plethodon cinereus. However, both Plethodon hoffmani and Plethodon virginia are more elongated and have darker venters (bellies) than Plethodon cinereus.

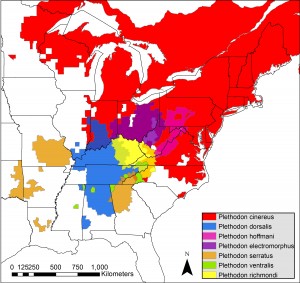

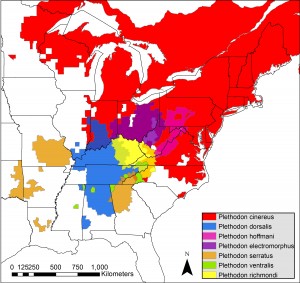

Now on to the species that have fairly large ranges. First and foremost the Eastern (Plethodon cinereus) and Southern Red-backed Salamander (Plethodon serratus). These species will be very difficult to tell apart, luckily their ranges do not overlap, with the Eastern Red-backed Salamander occurring north of the French Broad River and the Southern Red-backed occurring south of the French Broad River. If I am literally adjacent to the French Broad River I would remain skeptical as it is possible the species has been transplanted across the river by people or managed to float across on debris and set up a population.

Moving along we have the ZigZag Salamanders which are currently broken into a Northern (Plethodon dorsalis) and Southern (Plethodon ventralis) species. These species are essentially identical meaning the only way you can distinguish them is through genetic analysis or the location they are found. The red-backed salamanders look very similar but have more costal grooves. Also as the name of the Zigzag implies, the dorsal stripe is not as even compared to the Eastern and Southern Red-backed species. Also, as was noted in The Amphibians of Tennessee book by Niemiller and Reynolds, Zigzag Salamanders are often found in wetter conditions. I found this out first hand when I stumbled on what I thought was a large number of red-backed salamanders in standing water, however it turns out they were my first Zigzags.

Last but not least there are the Northern (Plethodon electromorphis) and Southern (Plethodon richmondi) Ravine Salamander. Again like a few other species pairs discussed the two can only be distinguished by location and in the few locations their ranges overlap, genetic analysis. Both species have a dark body with light brassy flecking similar to several other species I have mentioned, however it only overlaps with Plethodon welleri and Plethodon hoffmani. The brass/gold blotches will typically be more distinct in Plethodon welleri. The Ravine Salamanders are also more elongated then any other comparable species including the Zigzag and Red-backed Salamanders. Just as a general observation the Ravine Salamanders tend to not only be generally more elongated but their tails seem longer and more robust then similar species.

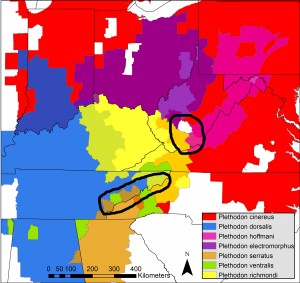

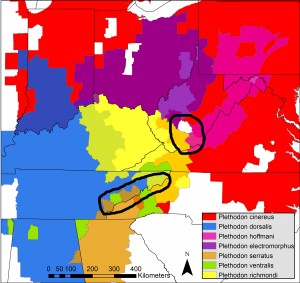

One major take home point is that many areas have low species richness and identifying species in these locations will be relatively easy. However, there are some areas which I have circled on the map below that have substantial richness and may require more information about habitat, morphology, or even genetics to reliably identify a salamander. Also, an important note. I made the colors transparent so the lighter colored orange is actually overlap between the red and yellow ranges, this is not Plethodon serratus as it might appear from a quick glance. The Plethodon serratus range color is a dark orange is restricted to south of Virginia.

Salamanders as a whole are just a very interesting group of organisms. There is substantial variation and species richness that often gets overlooked because they spend most of their time hiding in the leaf liter and under rocks and logs. However, as they have finally been getting some press recently, salamanders play a critical role in forest floor ecosystems. They also come in some very vibrant and attractive colors and can have very interesting personalities.

If you want to learn more about salamanders of the Appalachian Mountains, I highly recommend the following books:

The Amphibians of Tennessee

Salamanders of the Southeast

The Amphibians of Great Smoky Mountains National Park

My next post will hopefully be about a successful start to my field season!